26 September 2025

|

Author and podcaster Bibi Berki explains why she transformed her novel into an audio-drama

What do you see when you write? What do you hear? I always hear before I see. Interactions, conversations, confrontations. Words between people; toying, teasing, misleading. So much of the real landscape of fiction, after all, is in what people say to each other.

In the summer of 2010, I took my children to Lake Balaton, the shimmering playground of central Hungary, and stayed – as we had before – in a sleepy village called Szigliget, populated in the holiday season by foreigners like us.

I woke on the first morning after a heavy, difficult night (crushed by heat and small children) and lay in the sun alone in the bedroom, thinking. I recalled a brief, rather peculiar friendship I’d had had some years before and which had ended very suddenly. In those days I often pondered this relationship, tried to get my head around its strange trajectory. Out of nowhere, I imagined writing a letter to this person and the conversation that would come from it. And then reality evaporated, and I was suddenly following a dream path which took me far from the truth and into a fictional setting.

When I got home, I started writing a book about an email conversation between two women. Within this conversation was couched a friendship and an evolving adventure full of jeopardy and mystery – all of it from their own mouths.

When I finished it, a publisher friend recommended an agent who might be interested. The agent read the manuscript and called me in. He was surprisingly enthusiastic. “I’ve never stayed up half the night reading a manuscript before,” he said. I was astonished. Really?

There’s always a but and both he and I knew that the but was insurmountable. He didn’t like the format. The story within the story. It didn’t work as a novel, was the suggestion.

I was convinced that it did work as a novel, not, I think, because I was sold on the format, but because I didn’t entertain the idea of any other means of storytelling at the time. If I didn’t tell it this way, then what other way could there possibly be? Never mind that I was, in effect, writing a long conversation, interspersed with documentary fragments; surely that was readable, wasn’t it? It was just my take on the epistolary novel, after all.

Narratives made up of exchanged letters, or a series of documents or diary entries have always found a home in the novel. Les Liaisons Dangereuses, Herzog, The Handmaid’s Tale, We Need to Talk About Kevin – in different ways, these books all recount stories via documental sources. We are not just readers but researchers, poring over facts as they are presented.

In a dialogic format, where two voices ricochet off each other, we pick up what we can, aware that lives are being lived beyond what we are told. It requires an acquiescence from the reader, an acceptance that facts and feelings are trimmed according to the correspondent’s personality and intentions. What we often get in return is an intimacy and heightened sense of investment.

In other words, it’s a novel as audio drama. There is no all-seeing narrator to fill in the gaps. With that ubiquitous voice removed, lovers, friends, enemies “perform” their feelings while we listen in.

Your Most Avid Reader – my story of two women who collude in writing a version of British history – was never published. Instead, it became an audio drama. Or an audio story, to be more precise.

It makes perfect sense now, even if it never occurred to me as I wrote it after that holiday by Lake Balaton. Audio recording brings a beautiful, unexpected new life to a lot of fiction. Of course it does! Writing is a telling process, an inner voice projecting to an inner ear.

A story lives to be told and, as a producer, I have been astounded by the interesting new dimensions that a dramatic recording (one with judiciously used sound-editing) can give to a piece that hitherto existed on a printed page or on a screen.

The process of adapting a book for audio has not been unlike preparing it for publication: constant editing and fine-tuning, but this time in an effort to make it work for a listener – and, of course, for an actor. Actors hear what a writer is trying to say but then the words get sieved through their own psychological experience and come out with a new and different authority.

The writer, the actor, the producer, the sound editor, the listener: what seems like a fractured process is nothing of the sort. It’s a very natural and fluid means of making stories.

The recorded voices in Your Most Avid Reader startle me with their rightness. When I listened to the earliest takes by Georgina Sutton and Rebecca Charles, I felt like I was hearing the story for the first time. Their complex mosaic of a conversation sits so comfortably beside Mark Lingwood’s pitch perfect narration. For the few moments when a female narrator is needed, Claire Davies adds another subtle element to the mix. Somehow, they’ve all kept the adventure small and intimate, while the stakes remain high.

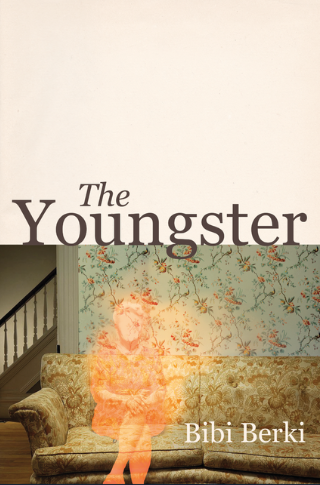

Bibi Berki worked originally as a news reporter but now writes on all kinds of subjects, though primarily film history. She is the author of The Watch (Salt, 2021) which was shortlisted for the Lucy Cavendish 2020 Fiction Prize. Her audio series, The Kiss, is one of Sight & Sound's recommended film podcasts. Her latest novel The Youngster (Deixis Press, £17.99) is available from all good book retailers . You can listen to Your Most Avid Reader here: https://soundcloud.com/user-986948053/sets/your-most-avid-reader

Bibi Berki worked originally as a news reporter but now writes on all kinds of subjects, though primarily film history. She is the author of The Watch (Salt, 2021) which was shortlisted for the Lucy Cavendish 2020 Fiction Prize. Her audio series, The Kiss, is one of Sight & Sound's recommended film podcasts. Her latest novel The Youngster (Deixis Press, £17.99) is available from all good book retailers . You can listen to Your Most Avid Reader here: https://soundcloud.com/user-986948053/sets/your-most-avid-reader

Read more about the experience of writing audio-first from author Rob Parker